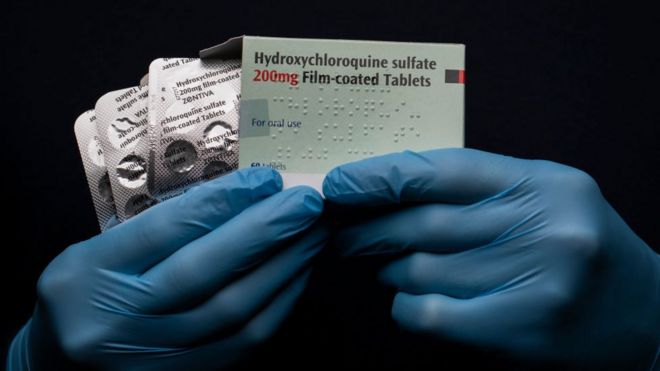

Hydroxychloroquine and Zinc seems to be working on coronavirus patients

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

India is reportedly "considering" a request by Donald Trump to release stocks of a drug the US president has called a "game-changer" in the fight against Covid-19.

Mr Trump called India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Sunday, a day after the country banned the export of hydroxychloroquine, which it manufactures in large quantities.

The two leaders are on friendly terms, and Mr Trump recently made a high-profile trip to India.

But is India really in a position to help the US? And does hydroxychloroquine even work against the coronavirus?

What is hydroxychloroquine?

Hydroxychloroquine is very similar to Chloroquine, one of the oldest and best-known anti-malarial drugs.

But the drug - which can also treat auto-immune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus - has also attracted attention over the past few decades as a potential antiviral agent.

President Trump said that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had approved it for treating coronavirus, something the organization has denied. Mr Trump later said that it had been approved for "compassionate use" - which means a doctor can give a drug that is yet to be cleared by the government to a patient in a life-threatening condition.

Doctors are able to prescribe chloroquine in these circumstances as it's a registered drug.

So, can India really help President Trump?

Hydroxychloroquine could be bought over the counter and is fairly inexpensive. However, its purchase and use has been severely restricted ever since it was named as a possible treatment for Covid-19.

On Saturday, India banned the export of the drug "without any exception". The order came even as the number of positive cases of Covid-19 spiked in the country. India has now recorded 3,666 active cases of the virus with more than 100 deaths, according to the latest data released by the ministry of health.

But now it seems the government could be reconsidering this stance, possibly following Mr Trump's call to Mr Modi. Local media quoted government sources as saying that a decision on this could be taken as early as Tuesday after considering what domestic requirements could look like in the near future.

But does India - one of the world's largest manufacturers of the drug - have the capacity to actually supply other countries as well?

Yes, according to Ashok Kumar Madan, of the Indian Drug Manufacturer's association.

"India definitely has capacity to cater to both global and local markets. Of course, domestic considerations must come first, but we have the capacity," he told the BBC.

- Why is Trump so keen on malaria drug to treat coronavirus?

- India coronavirus doctors 'spat at and attacked'

- Coronavirus outbreak could cripple India's economy

Mr Madan also denied reports that China had severely limited the export of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) that is used to manufacture hydroxychloroquine. He acknowledged that 70% of all the APIs needed by India to manufacture drugs come from China, but said that supplies from China had steadily continued "by both sea and air".

But does it work?

Many virologists and infectious disease experts have cautioned that the excitement over hydroxychloroquine is premature.

"Chloroquine seems to block the coronavirus in lab studies. There's some anecdotal evidence from doctors saying it has appeared to help," James Gallagher, BBC health correspondent, explained.

But crucially there have been no complete clinical trials which are important to show how the drug behaves in actual patients, although they are under way in China, the US, UK and Spain.

Even so, some are sceptical about how successful they will prove to be.

"If it truly has a dramatic effect on the clinical course of Covid-19 we would already have evidence for that. We don't, which tells us that hydroxychloroquine, if it even works at all, will likely be shown to have modest effects at best," Dr Joyeeta Basu, a senior consultant physician, told the BBC.

REUTERS

REUTERS

Raman R Gangakhedkar, a senior scientist with the Indian Council of Medical Research, said the policy at the moment is that the drug is not to be used by everyone.

"It is being given to doctors and contacts of lab confirmed cases. When their data will be complied only then a call can be taken whether it should be recommended to everyone," he told reporters last week.

Despite the fact trials are yet to conclude, people have begun to self-medicate - with sometimes disastrous consequences.

There have been multiple reports in Nigeria of people being poisoned from overdoses after people were reportedly inspired by Mr Trump's enthusiastic endorsement of the drug.

An article in the Lancet medical journal also warns hydroxychloroquine can have dangerous side-effects if the dose is not carefully controlled.

This lack of certainty has prompted social media sites like Facebook and Twitter to delete posts that tout it as a cure - even when they are made by world leaders.

Excitement around hydroxychloroquine for treating COVID-19 causes challenges for rheumatology

Published:April 01, 2020DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30089-8

Excitement about a potential new treatment for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic currently engulfing the world is causing problems for patients with arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), who routinely use the drug to control their symptoms.

The antimalarial drug chloroquine and its safer derivative hydroxychloroquine have been used since the 1940s to treat autoimmune disorders, says Thomas Dörner, a rheumatologist at the Charité University Hospital in Berlin. Though the drug is rarely used for rheumatoid arthritis, around two-thirds of patients with SLE in Europe use hydroxychloroquine to manage their symptoms, and it is the only known therapy so far for primary Sjögren's syndrome, he says.

But the drug has also attracted attention over the past few decades as a potential antiviral agent, currently as a possible treatment for the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that causes COVID-19. Reports from China found that chloroquine could inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro, and showed apparent efficacy in treating COVID-19 in humans. A small non-randomised trial in France also found hydroxychloroquine to be a promising potential treatment.

The findings have prompted many, including US President Donald Trump, to tout hydroxychloroquine as a game-changer in the fight against COVID-19. The US Food and Drug Administration has designated hydroxychloroquine for off-label, compassionate use for treating COVID-19, and WHO added the drug to its large global SOLIDARITY trial to test a variety of potential treatments. But virologists and infectious disease experts caution that the excitement is premature.

“Whether hydroxychloroquine works in vivo is not proven for any virus, and in fact in randomised controlled trials against a number of viruses, including influenza, it doesn't work at all,” says Douglas Richman, a virologist and infectious disease physician at the University of California, San Diego. “It's my personal prejudice that this is also going to be the case with coronavirus.”

Hydroxychloroquine has been studied as a possible antiviral for approximately the past 40 years, says Richman. The mechanism of action is not entirely clear, but it is known to decrease the acidity in endosomes, which might prevent the endosome from releasing the virus into the cytoplasm.

Hydroxychloroquine has shown activity in vitro against many viruses, including influenza and coronaviruses, but that has largely failed to translate into success in either animals or humans. In 2005, the drug showed in vitro activity against SARS-CoV, which is closely related to the current pandemic virus, but it failed to decrease viral load in mice, and clinical interest drifted away, says Christopher Tignanelli, a surgeon at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, who is involved in clinical trials of COVID-19 treatments.

“There is not a huge amount of pre-clinical data for this drug,” says Tignanelli. “It's mostly test-tube and anecdote.”

Despite the absence of strong evidence, some people are already attempting to self-medicate with the drug, with disastrous consequences. Hydroxychloroquine can have dangerous side-effects if the dose is not carefully controlled, and cases of chloroquine poisoning have been reported in Nigeria and the USA.

Additionally, the sudden interest in hydroxychloroquine has led to reports of shortages for patients who rely on the drug to treat their autoimmune disease. Kaiser Permanente, a major health-care network in the USA, is no longer filling routine prescriptions for chloroquine.

“It's a challenge for us and for our patients,” says Dörner. “When I write a prescription now, I tell my patients that they might need to go to several pharmacies before they get it filled.”

The Lupus Foundation of America has called on drug manufacturers to increase the production of hydroxychloroquine, to ensure that patients with SLE who need the medication will still be able to access it while it is being investigated for COVID-19. “For many people with lupus there are no alternatives to these medications,” the Foundation said in a statement.

Although the existing evidence is thin, it is promising enough to warrant further study, says David Boulware, an infectious disease physician at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. “When someone is sick in hospital, we throw the kitchen sink at them, but we don't always know if it works,” he says. “That's why we need clinical trials.”

Boulware is leading a trial to investigate whether hydroxychloroquine could be efficacious as a post-exposure prophylactic to prevent the development of the disease, and to prevent progression of the disease to avoid admission to hospital. The trial (NCT04308668) has already enrolled around 25% of its subjects. Initial results are expected within 3–4 weeks.

Though he is skeptical of its efficacy, Richman fully supports further research to establish whether hydroxychloroquine is a good option for treating COVID-19. “It's imperative that good RCTs are implemented to get answers one way or another,” he says.

No comments:

Post a Comment