Why Mast Rake?

by Reuel Parker

October 2, 2013

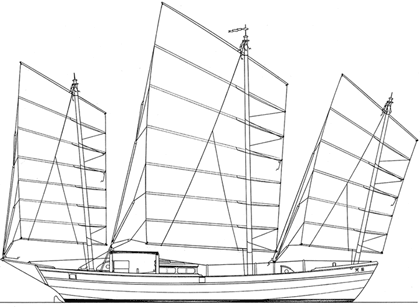

A LORCHA sail plan, based on 16th-century Chinese/Portuguese technology.

A common question people ask me is why masts are raked, and why, in many instances, they are raked differently. In ocean-sailing three-masted Chinese Junks, for example, the main mast is often nearly vertical, but the fore and mizzen masts rake strongly away from the main.

The simple answer (really evading the question) is that it’s traditional, and that it looks good. If you look at drawings, paintings and many surviving historical vessels, particularly from times previous to the mid-nineteenth century, you will note strong mast rake. A common factor among most of these vessels is the absence of standing rigging—the masts are usually free-standing.

To begin with: Because the primary vector of sail drive is forward, the overhanging weight of an aft-raked mast helps counter-balance this vector. If a jib is employed, this mast weight helps provide luff-tension. Because a raked mast bends aft, luff-tension will straighten it, whereas a vertical mast would bend forward, compromising mains’l shape. Thus: Cantilevered mast weight aft counters sail drive forward and helps tension forestays. Free-standing raked masts can also be “curved” (bent aft) more easily to flatten sails when sheeting in, creating a smaller sail chord when beating to windward. Many modern “go-fast” racing sailboats use hydraulic backstays to achieve this, when traditional vessels with free-standing masts simply used the main sheet. It is theorized that the raked sail luffs even provide a small “vertical lift” vector, but I personally doubt the effectiveness of this, except possibly on ultralights.

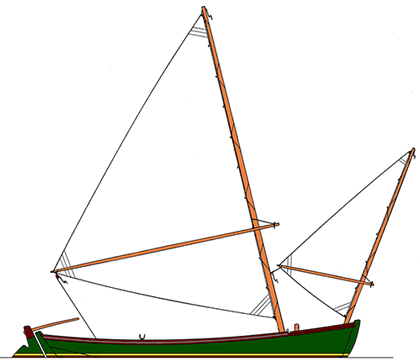

A 16′ Eastern Shore Stick-up crabbing skiff.

Some masts are raked strongly forward. Examples include Chinese Junks, New York Harbor lighters (called “periaguas”), and Chesapeake Bay log canoes and crabbing skiffs, the Eastern Shore “Stick-up” being an example.

This unlikely-looking sail plan has unique and unanticipated properties: first, the mast steps and partners are out of the cockpit or fish hold; second, the large gap between sails allows them to function independently of each other when close-reaching or beating; and third, the fores’l is “self-selecting”—it will automatically jibe to the most effective side—when sailing off the wind. Marine historian Howard Chapelle noted that it was claimed that stick-ups could work to windward in very strong winds under fores’l alone, something which seemed theoretically impossible!

Independent of the free-standing factor, mast rake provides longer sail luff length without equivalent vertical mast height & weight aloft (including heads’l luffs especially). This translates to more sail power for less weight and windage aloft, and results in all-around improved performance.

Sails “hang” from a raked mast instead of wanting to collapse against it—consequently providing better sail shape, particularly if the sail is boomless. Flatter sails & better shape are also due to longer sheet-lead angles, especially for overlapping (boomless or lug-rigged) foresails. And sails, with or without booms, automatically swing to the deck centerline for easier furling & reefing. This may also make for easier jibing.

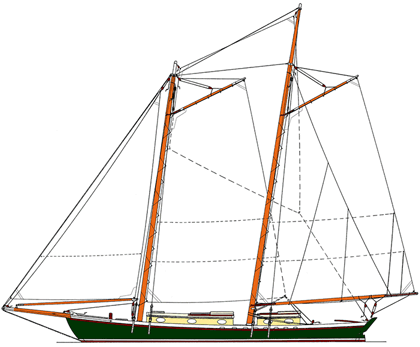

A 45′ Virginia Pilot Schooner based on Isaac Webb’s DREAM from 1833.

In schooners with boomless foremasts, halyards hang well aft of the mast base, and can be used to lift cargo and launch boats more easily, swinging clear of masts & rigging. The consequent location of mast-partner and -step further forwardfrees up critical deck, cargo hold and cabin space, and provides awider shroud base in some instances. This last item is especially valid when using halyards as temporary backstays—a common practice on vessels with free-standing masts.

A critical consequence of a raked mast is the more “acute angle” between mast and boom. Boom-ends are thereby elevated off the waterwhen reaching and running, and are less likely to trip, or break, in large seas. This is particularly true for schooners with long overhanging main booms. And most vessels with strongly raked masts have less pitching motion, because mast center-of-gravity is located further aft, above the hull’s location of maximum buoyancy.

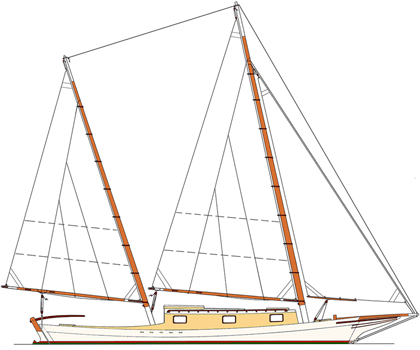

A 33′ Chesapeake Bay BROGAN, adapted from early 19th century Oyster

Boats.

A final added advantage of sails on raked masts is that they can be more easily lowered when running off the wind, due to the wind helping to push them down. This is even more effective if the masts are free-standing.

As for why masts are raked differently, almost any yacht designer will tell you that parallel masts appear to be converging, visually, and should always diverge slightly to avoid this. The Herreshoffs, in particular, made this clear in their writings.

An excellent contemporary example of a strongly raked mast may be seen on the ocean-racing catamaran ENZA (Eat New Zealand Apples), which won the original Jules Verne Around the World Trophy. The mast rake was actually a consequence of lengthening the original cat without relocating her mast step… but her crew came to believe that the strongly raked mast made her faster and easier to sail… and it does look good!

No comments:

Post a Comment