CAPRICE and GHOST

The unlikely return of the Sound Interclub class

MATTHEW P. MURPHY

CAPRICE (left) and GHOST were part of the 28-boat Sound Interclub fleet built by Henry B. Nevins during the winter of 1925–26. The class raced on Long Island Sound for more than a decade before being eclipsed by the larger International One Design.

MYSTIC SEAPORT/ROSENFELD COLLECTION

CAPRICE was originally name OPAL II and owned by Charles H. Appleby. By 1939—the year of this photograph—she had been renamed HELJAK. Here she’s outpacing Sound Interclub No. 1, which was then named ARIEL.

In the autumn of 1925, a group of Long Island Sound yachtsmen met to discuss their growing need for a modest-sized daysailer. They sought a boat of similar proportion to a 6-Meter, but smaller, less expensive to build, and easier to sail. The new boats would be simple enough to be handled by junior yachtsmen, but exciting enough to provide good competition for veteran sailors. They would be well built, beautiful, and reasonably priced. The group, led by Carroll B. Alker of the Seawanhaka Corinthian Yacht Club, reviewed a number of proposals, but settled decisively on one from Charles Drown Mower.

Mower (pronounced as in lawnmower), a native of Massachusetts, had learned yacht design from the best practitioners of the day. In the late 1800s he’d studied naval architecture under Arthur T. Binney and began his career drawing dories for the racing fleets of Boston’s North Shore. He also worked with the legendary B.B. Crowninshield, whose rich portfolio of designs included the Dark Harbor 17½-footers—one of the most enduringly popular knockabout sloops of all time. In 1911, Mower moved to Philadelphia, where he began designing for the New York market, and eventually became chief draftsman for the well-known Henry B. Nevins Shipyard on City Island, New York. He also served as the design editor for The Rudder magazine. Mower was an accomplished designer as well as a skilled draftsman with a wide-ranging repertoire by the time the New York consortium came to him with ideas for a new one design.

Mower’s new sloop measured 28′9″ overall, 19′ on the waterline, and 7′6″ at the beam. The approximately 6,000-lb hull (2,500 lbs of which was in the external lead ballast) was driven by 425 sq ft of sail carried in a colossal main and a tiny jib. Under this towering rig, the boats of the new class promised to be fast. And they were, indeed, beautiful.

HOLLY PASTULA

Charles D. Mower was a designer of wide-ranging talent who got his start on the North Shore of Massachusetts. He was, for a time, chief designer for Henry B. Nevins.

Nevins built the boats—28 of them in all—over the winter of 1925–26 at the cost of $2,400 each. That included one suit of sails built by Ratsey & Lapthorn, the great British sailmakers who by then had a thriving loft on City Island. To ensure identical hull shapes, the whole fleet was framed on a single building jig. They had white oak keels, frames, and stem, and Alaska yellow cedar planking fastened with bronze screws. According to William Swan, who wrote about the boats in Edwin Schoettle’s classic anthology, Sailing Craft, the execution of the construction, and particularly the solid mahogany trim, exceeded the specifications of the owners.

The class was named the Long Island Sound Interclub, or Sound Interclub, for short, for the boats were intended to race among various clubs on the Sound—and beyond. Several owners bought them for their kids, and some installed toilets under a transom berth in order to allow short cruises. A few were never meant to race, but the vast majority of the 28 were keen competitors for more than a decade. Notably, several of the boats were shipped out to Bermuda on multiple occasions from 1929 through 1935 for team-racing championships against the Bermuda One-Designs—a Burgess-designed sloop of similar proportions. The Sound Interclubs might also have been meant to race against their near-sisters, the Alden-designed Triangle-class sloops of Marblehead, though I’ve not found any record of that actually happening.

JOHN KELLY

C.D. Mower’s granddaughter, Holly Pastula, found this model of a Sound Interclub among a collection of her grandfather’s belongings stored in her attic. The model is believed to be part of the original design proposal.

The New York Times of March 13, 1929, reported that four boats and crews had been chosen for the first of the Bermuda contests, which was to be sailed April 4–6 that year. The boats—AILEEN, JANE, ANNE, and BLUE STREAK—were then owned, respectively, by Cornelius Shields, Fred Gade, Walter Pierson, and Ralph Manny. All would be sailed by their owners—save for ANNE, which was under the command of William Swan. Lillian Gade, wife of Fred, was on the crew roster of JANE, along with Charles H. Appleby, who was the original owner of Sound Interclub No. 12, OPAL II. Some 65 years later, OPAL II, by then named CAPRICE, would grab my attention as she sat neglected in a Maine boatyard. I didn’t know it at the time, but CAPRICE was one of only a handful of survivors of the once-great Sound Interclub class—and the most original.

In the autumn of 1993, a year or so after joining the editorial department of this magazine, I received a telephone call from technical editor Maynard Bray telling me of a forlorn 28′ sloop sitting on land at a nearby boatyard. I was looking for a boat at the time. But, then, I was always looking for a boat in those days. Kid in a candy store, and all that. So Maynard and I went to inspect her.

DAVID B. WARREN

Beginning in 1939, ten or so Sound Interclubs migrated to Lake George, New York, where they raced for nearly two decades.

What we found was a boat on the edge. The canvas cover had blown off the cockpit, and the bright-finished coamings had begun to weather and peel. The painted canvas decks were cracked and torn. Word around the yard was that the boat had sunk on her mooring. The owner lived far away, and had made an attempt at rehabilitating her, but his toddler son had knocked over a gallon of paint in the cabin, and he’d thrown up his hands in frustration and walked away. The boat was very much for sale.

There was no name on the transom, but a storage receipt found aboard identified her as CAPRICE, and a bronze builder’s plate indicated she’d been built by Henry B. Nevins. The mainsail carried the number 12. Most astonishingly, all of her original hardware was in place. This included a pair of vernier-style winches mounted through the deck, with cranks in the cockpit and low-profile, inconspicuous wire drums on the deck; these were for fine-tuning the jib after rough-trimming it with the rope end of the two-part sheet. She was simple and unadorned, save for the elegant and understated mahogany trim around the top edge of her cabin (see related article, page 49).

I don’t recall why, but I didn’t buy her then. Instead, I bought a Triangle and spent the next several years rebuilding that hull in fits and starts, learning as I went. And the deeper I got into that project, the more the vision of the more refined Sound Interclub haunted me. I kept track of her even after Bryan Kearns of Deer Isle, Maine, bought her. He had a soft spot for pre–World War II boats of any type, and was in the process of building a castle-like boathouse in which to shelter his growing collection.

DAVID B. WARREN

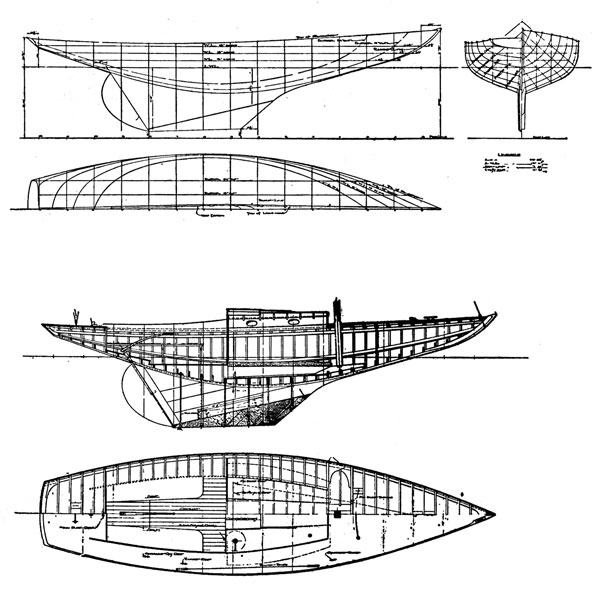

Much of C.D Mower’s archive was destroyed by fire. The only known surviving lines for the Sound Interclub are the ones shown here, which appeared in Edwin Schoettle’s Sailing Craft, as well as in the design sections of The Rudder and Yachting magazines in 1925. Restorer Reuben Smith found these lines to differ markedly from the boat as-built, which led to a laborious process of documenting the true shape before restoration could begin.

In 1999, I heard through the grapevine that Bryan had decided to sell CAPRICE. I called him. He told me that he was in fact letting the boat go, as he hadn’t sailed her—he’d just bought her to see her preserved. To that end, he’d had her shrink-wrapped—a decision that clearly had saved the boat from further deterioration. Save for a hole punched in the bow by a careless trailer operator, her condition had not changed since my first encounter with her five years earlier.

This time I leapt at the chance. I sold the Triangle project and spent the following few months of weekends in Bryan’s yard stripping and refinishing CAPRICE’s hull, patching the hole, and removing the Wankel air-cooled rotary engine from the cockpit. Later, during a particularly mild winter (T-shirt days in January) and working under a bow-roof shed, I stripped the decks of their canvas and re-covered them. I stripped the brightwork, cleaned up the interior a bit, and by spring she was ready—or ready enough. CAPRICE was launched in late June 2002, for the first time in 13 years. In a particularly poignant coda to this initial effort at rehabilitating her, photographer Benjamin Mendlowitz, patrolling the western end of Eggemoggin Reach, spotted us sailing under the Deer Isle Bridge on this maiden voyage and captured an image that would grace his Calendar of Wooden Boats the following April. Gimlet-eyed observers of that photograph have berated me for the fact that the jib is led through makeshift rope fairleads looped through the turnbuckles, as I’d not yet reinstalled all of the hardware. Summer couldn’t wait.

Over the next few seasons, with proper jib fairleads, CAPRICE proved to be one of the finest-performing boats I’ve ever sailed. The exquisite proportions of her shape, superstructure, hardware, and rig are a metaphor of sorts for her handling qualities: She balances beautifully in a modest breeze, requiring just a finger on the tiller. And she ghosts along in the lightest of zephyrs. I recall one evening when I invited the yacht designer Paul Gartside for an after-class sail at WoodenBoat School. It was a near-windless evening, but the big rig drove CAPRICE through the slightest breaths of air. “It’s like she’s on ball bearings,” Paul whispered incredulously.

COURTESY OF REUBEN SMITH

CAPRICE (foreground) required new frames, floors, and backbone timbers, but much of her original planking remained intact. GHOST was in far worse condition, and required near-total rebuilding.

But all was not well beneath, and I knew it was a matter of time before CAPRICE would need the big job. Years ago, she’d been sister-framed on the port side in order to repair a row of broken frames, and now the sisters were breaking, too. Although the planking remained tight and solid, the bronze fastenings were deteriorating. The lower edge of the cabin trunk was also suspect. I faced the daunting prospect of a rebuild while starting a family—and feeling the urge for a larger cruising boat.

And so I listed CAPRICE for sale, on-again, off-again, with no takers over the course of a few years. It was a tough sell: The boat looked fine from the curb, but she really needed a deck-off restoration. The sheer had flattened a bit amidships, and the hull would have to be tweaked to its original shape before she received a complete and necessary reframing. She’d also need new floors, cabintop repair, and keelbolt inspection. I knew that giving her away might spell her doom, and dreamed of finding an owner who understood her value and who would commit to a thorough restoration. This would not be a job for the faint of heart—or finances. With no takers, I resolved to mothball her, as Bryan Kearns had done, and to restore her someday. That’s when Reuben Smith called.

COURTESY OF REUBEN SMITH

The newly rebuilt CAPRICE receives her finishing touches in 2011, while the barely visible GHOST just beyond her is still in the throes of restoration.

Reuben is a boatbuilder in Warrensburg, New York, and a native of the Adirondack region. We’d known each other for years, since the days when he rented the former shop of George Shiverick, a legendary 19th-century catboat builder in Kingston, Massachusetts. Before that he’d worked at the Hull Lifesaving Museum in Massachusetts, and before that worked from a box trailer aptly named Tumblehome Boatshop. He’d later moved, with his wife, Cynde, to upstate New York—his childhood home. When he contacted me in 2009, he was working for Hall’s Boat Co. on Lake George, New York, and would later establish his own shop—Reuben Smith’s Tumblehome Boatshop. His phone call unleashed a torrent of activity that would, ultimately, bring not only CAPRICE back to life, but the Sound Interclub Class as well.

Reuben had a client who had become enamored of the Sound Interclubs through a single photograph. This client, John Kelly—an IBM research executive and longtime summer resident of Lake George—had recently had Reuben restore for him a 1936 Gar Wood runabout. John, a dogged researcher in technology by profession, had assembled a file of material on the Gar Wood, and in that file was a photograph of the Gar Wood’s original owner in a stunning sailboat. The sailboat caught John’s attention, and he asked Reuben if he could identify it. “That’s a Sound Interclub,” Reuben said.

MATTHEW P. MURPHY

CAPRICE (right) and GHOST sail on Lake George, late summer 2014.

But what in the world was it doing on Lake George in the late 1930s?

Cornelius “Corny” Shields was a stalwart of the Sound Interclub Class who’d made his mark sailing AILEEN (No. 25). On one of his many trips to Bermuda for the annual team-racing event in Sound Interclubs, he’d encountered a 6-Meter sloop called SAGA designed by the great Norwegian yacht designer Bjarne Aas. Shields was immediately taken with SAGA, and envisioned her as the basis for a new class of boat—a class of great beauty and performance that would entice sailors from all over the world to compete on an equal footing…an International One Design.

That was the birth of the IOD, which achieved its goal and has remained popular to this day with fleets in Scandinavia, the United States, Bermuda, the U.K., and Canada. The IOD’s immediate appeal, however, spelled the end of the Sound Interclub fleet on Long Island Sound, as the best competitors from the older class defected to the new one.

Back when I owned CAPRICE, I thought the story ended there, and that the Sound Interclubs had scattered to the wind. But it turns out that more than a third of them went to Lake George. They were all sold for $2,100, and several of them arrived in 1936 by railroad car; more followed soon after.

Lake George is located 200 miles north of Larchmont—the epicenter of sailing on Long Island Sound. The lake is 32 miles long and 1 to 2 miles wide, and is fringed by tall mountains and summer homes. Since 1909, it has been home to the Lake George Club—a golf, tennis, and sailing establishment. Sailing came to the fore at the club in 1934, when a group of General Electric engineers and local entrepreneurs brought in a fleet of used Cape Cod Knockabouts. A year or two later, they graduated to Star-class sloops, and by 1936 found themselves wanting something bigger and more challenging. The timing was perfect: the Sound Interclubs had just been listed for sale.

MATTHEW P. MURPHY

John Kelly, owner of CAPRICE and GHOST, provided the vision and energy for the ongoing revival of the Sound Interclub class. To windward is Cynde Smith, wife and business partner of builder Reuben Smith.

The class was an immediate hit on Lake George, and proved to be well adapted for the modest breezes there. Hibby Hall, an entrepreneur and founder of Hall’s Boat Company—an iconic Lake George boat-service facility—led in the standings for years in TEAL (No. 10). Harold Pitcairn in PICAROON (No. 21) was always nipping at his heels. It was a closely contested fleet through 1958—the last year of recorded racing results.

A few of the boats continued to sail on Lake George for years after the racing ended. Hall’s TEAL along with NIGHT HAWK (No. 26) were sold to the Canoe Island Lodge, where they took resort guests on excursions through the early 1980s. Louisa Watrous, intellectual property manager at Mystic Seaport in Connecticut, grew up on Lake George and spent summers of her youth sailing expeditions in these boats. (It was she who documented much of the history retold here.)

After the early 1980s, the trail runs cold. The Canoe Island Lodge sold its pair of Sound Interclubs at that time, and then the rest of the fleet finally did scatter to the wind. After that, there wasn’t much talk about them. The Lake George Club had moved on to a succession of other one designs—Rainbows, J-24s, and then J-22s, and the old Sound Interclubs were all but forgotten, save for a few photos. “If there’s a class that got overlooked,” said Reuben Smith, “it’s this one.”

So, when John Kelly rediscovered the class in that archival photograph, he began a quest that led him to the boat under the bow-roof shed in my driveway in Maine. “I had never seen John like that,” said John’s brother, Mike, of John’s commitment to that research project. “He wanted to know everything about that boat.”

We came to quick terms when John visited. I was thrilled for CAPRICE’s future, and John was blown away by her originality. After he left, I packed the boat up and shrink-wrapped her for the long trailer ride out to Lake George, and I kept in touch with the project via photographs. The next time I saw her in person was at The WoodenBoat Show in Mystic, Connecticut, to which John and Reuben had trucked her for display in 2011. They launched the boat and had her in the water and sailing around the show venue. And, incredibly, on a nearby trailer they had the partially restored GHOST—a once near-derelict Sound Interclub that I’d inspected years before in Rhode Island and deemed too far gone to save. John had acquired her soon after buying CAPRICE. The boats, both now restored by Reuben and crew, are identical stable-mates at John’s home on Lake George.

MATTHEW P. MURPHY

Sean O’Neill (dark shirt) takes a turn at the helm of CAPRICE, while John Kelly Jr. looks after the jib. Sean and Reuben have worked together for decades, in three different shops, and Sean was an indispensable part of the Sound Interclub restoration crew.

But John’s quest did not end there. In the years since he purchased CAPRICE, he has traveled thousands of miles chasing Sound Interclubs and their history. He’s purchased one more of them, and is considering another in the Lake George area, which he’d simply store as a reference. His third boat is AILEEN, arguably the most famous of the fleet—the one in which Corny Shields won so many championships on Long Island Sound. There’s one other Sound Interclub still known to be in existence: BANDIT (No. 13). It was featured on this magazine’s Save a Classic page in 2001 (see WB No. 159), and subsequently found a new home.

Up until 2005, there was one other Sound Interclub, SIREN (No. 27), which sailed from the Southern Yacht Club on Lake Ponchartrain in New Orleans (a total of five Sound Interclubs had made their way there in 1937). She sank at the dock in Hurricane KATRINA, and was declared a total loss. Louisa Watrous told me that, for weeks afterward, the lost boat’s owner, Bobby Killeen, would go to the dock and look down at the water, mourning. John Kelly’s interest in the class was “in the nick of time,” Louisa said. “It came just before everyone with firsthand experience with the boats vanished.”

It was not only the ownership and racing histories of the class that were on the brink of oblivion: The shape of the hull itself also hung in the balance. As CAPRICE’s sheer flattened over the years, the boat’s midsections began to straighten—a common occurrence in older boats, and one often made right by referring to the original drawings. But there were no surviving original lines for the Sound Interclub. There had been a set published in Shoettle’s Sailing Craft, but Reuben determined quickly that these were not buildable—and that the forward sections were markedly shallower than as built. “This wasn’t surprising,” Reuben told me. He suspects that Mower may have deliberately altered the plans for publication, in order to deter plagiarism.

MATTHEW P. MURPHY

The view from the cockpit: The Sound Interclubs have an unusually deep and large cockpit, while also having excellent visibility and comfort. Reuben Smith is at the helm, and John Kelly on the mainsheet.

For John and Reuben, there followed a marathon project of determining the proper hull shape of a Sound Interclub. This led them to connect with Holly Pastula, granddaughter of C.D. Mower, who had found a model of her grandfather’s in the space above her garage. John and Reuben suspect it is the original proposal model presented to Carroll B. Alker and his compatriots at the time the class was conceived. This model, the measurements from CAPRICE, and some extrapolation culminated in the “truing” of the lines. “The shape is everything,” Reuben said. “John is relentless. We probably spent 300 hours figuring out what it is.” The resulting body of work is trademarked as “True ISC.”

With the hull shape determined, the woodwork commenced. The crew at Reuben’s shop began by removing CAPRICE’s deck and slowly, carefully, adjusting the shape. “We made the hull plastic enough to work it back into shape,” Reuben said. He then placed three molds in the boat to hold that shape during its complete reframing with steam-bent white oak. The boat also received a new sprung keel of white oak, and a new trunk cabin—which was built by Reuben’s father, Mason, at his shop in Blue Mountain Lake, New York.

MATTHEW P. MURPHY

CAPRICE in her element: 10–12 knots, and flat seas. The colossal sail plan drives the hull in the lightest of zephyrs.

There were no mysteries in CAPRICE’s hardware or its placement. Period photographs confirmed that her existing complement was as it had been in her heyday. GHOST, however, had been altered, and would have posed deep challenges had it not been for the originality of her sister. “It really took CAPRICE to get a bearing on the details,” John said.

CAPRICE’s original rig had been lost in a boatyard fire years before I acquired her, and it was replaced with a beautifully built copy rigged with, presumably, the original hardware. This rig was intact, and required no modification. Sperry Sails in Marion, Massachusetts, made new sails for GHOST and CAPRICE from cream-colored Oceanus cloth. They are beautifully built, and are in keeping with John’s aim for originality: They feel like canvas, and are built in narrow panels. The mainsail is crosscut, the jib is miter-cut, and the boltropes and grommets are hand-sewn. For GHOST, J.M. Reineck & Son built copies of CAPRICE’s vernier winches, and Elco supplied well-hidden electric motors for each of the boats—a necessity for getting in and out of the narrow slips from which the boats sail.

In September of last year, I made a long-discussed trip to Lake George to sail the restored boats. Settling in at the helm of CAPRICE brought me right back to that spring day in 2002 when, with a group of friends, I sailed her for the first time and Benjamin Mendlowitz recorded the moment for his Calendar.

The halyards and jibsheets all lead to the forward end of the cockpit, leaving the after portion clear for the helmsman and mainsheet. She accelerates quickly upon sheeting in the main and jib, and has an awesome feeling of momentum that belies her 28′. Once moving, she begs for just a finger or two on the tiller.

MATTHEW P. MURPHY

The stablemates, CAPRICE and GHOST, at the end of an afternoon on the lake.

John asked me at one point whether CAPRICE is different from when I owned her. Impulsively, I told him she wasn’t. The feel of the helm, the leads of the sheets and halyards, the ergonomics of her cockpit, the smell of the boat: It was all the same. Later, I was concerned that my answer might have offended him, given all of the thousands of hours of work spent on her and GHOST’s rehabilitations. Clearly, she’s cleaner and more crisp—and better maintained. But one of the things that drew me to CAPRICE in the first place was her originality and hard-won patina. John, Reuben, and crew have preserved that, while correcting her shape and eliminating the deep structural problems that would have soon spelled the end of the boat had she been kept sailing without rebuilding. Likewise, she may have slowly melted into the land if left ashore. She’s restored, but she’s not a new boat. She and her sister, GHOST, are the same boats that rolled out of the Henry B. Nevins yard in 1926, ready to take on the best sailors on Long Island Sound.

Matthew P. Murphy is editor of WoodenBoat.

The Project of a Lifetime: The Restorer’s Perspective

MATTHEW P. MURPHY

Reuben Smith, who led the restorations of the Sound Interclubs GHOST and CAPRICE, enjoys an outing in CAPRICE on Lake George. GHOST is in the background. “The experience of being in one boat while looking at the other,” says Reuben, “keying off the other, reacting to puffs, crossing tacks, is so much more than just sailing.”

The restorations of CAPRICE and GHOST were once-in-a-lifetime projects. The demands of the client, the community of people who took a serious interest in the job, and of the boats themselves were higher than I had ever experienced. Every decision required an analysis before I felt the confidence to proceed. Although it was a daunting challenge to live up to these expectations, it was also a moment for which a boat restorer lives. We were fortunate to be able to tap some of the most highly skilled people in the greater wooden boat building community, including Jim Reineck and his bronze hardware; sailmaker Ben Sperry; fastening manufacturer Goulet Specialties; my boatbuilder-father Mason Smith; sailboat-restoration guru Andy Giblin; electric motor manufacturer Elco, and many more.

While I work in an industry where people are always excited by what we do, I have never been around a project that had aroused so much interest and excitement. Over the first few months of researching and starting the restoration of CAPRICE, an amazing array of people showed up with a history and passion for the boat. In fact, there was so much interest that we decided to hold a summit at Hall’s Boat Corporation, in the winter of 2010, when the restoration was just barely underway. Fifty-odd people showed up from as far away as Southeast Massachusetts and the tip of Long Island—as well as from all around Lake George. We had Larry Jacobsen, who had sailed GHOST back in the 1950s; and Jerry Thornell, who logged hundreds of days sailing a Sound Interclub and dismasted one on Lake George. Dave Warren, Rik Alexanderson, Louisa Watrous, and the descendants of Hibbard Hall showed up with stories, photos, and even old home movies of the boats sailing. Not only were the boats out racing back in the 1940s, but we found photos of the Lake George fleet anchored in a quiet bay, rope ladders over the sides, towels drying on the booms, and a campfire on the shore. The community of interest created a climate of charm around the project, and fed a wonderful serendipity: When we needed an answer, or a part, it showed up, on cue, time and again.

No comments:

Post a Comment